Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

Karlo Grigolia, a reformer of Georgian sculpture and significant figure in Georgian art history, has only recently been recognized by Georgian society. Three exhibitions featuring his artistic legacy were organized between 2019 and 2023. Among them, the D. Shevardnadze National Gallery of Georgia held Karlo Grigolia's first retrospective exhibition “Forbidden Art” in March 2023, curated by G. Grigolia, and co-cureted by M. Chikvaidze. The exhibition was presented by the Cultural Center "Atinati". From the day of the exhibition opening, Georgian society became collectively intrigued and respectful of Karlo Grigolia's work, as was evidenced by the responses on social media. It was inconceivable to many that a sculptor of his stature could have stayed so unknown within the country. Due to political circumstances, he remained a marginalized sculptor for decades, keeping his work hidden from the public eye and showing it only within professional circles. It was the price Grigolia paid for nonconformity through his rejection of the framework of socialist realism and opposition to Soviet culture.

Karlo Grigolia - the Beginning

Grigolia’s creative path spanned 64 years. He was born in 1927 in Senaki, Georgia. In 1950, at the age of 23, he enrolled at the Tbilisi State Academy of Art. His teachers were the masters of Soviet Georgian sculpture and unequivocally brilliant sculptors Nikoloz Kandelaki and Shota Mikatadze. Karlo Grigolia was one of a number of students who tried to develop their own individual processed forms related to plastic art, which were distinct from Soviet art, but in parallel with the educational programs of the Academy of Art as approved in Moscow.

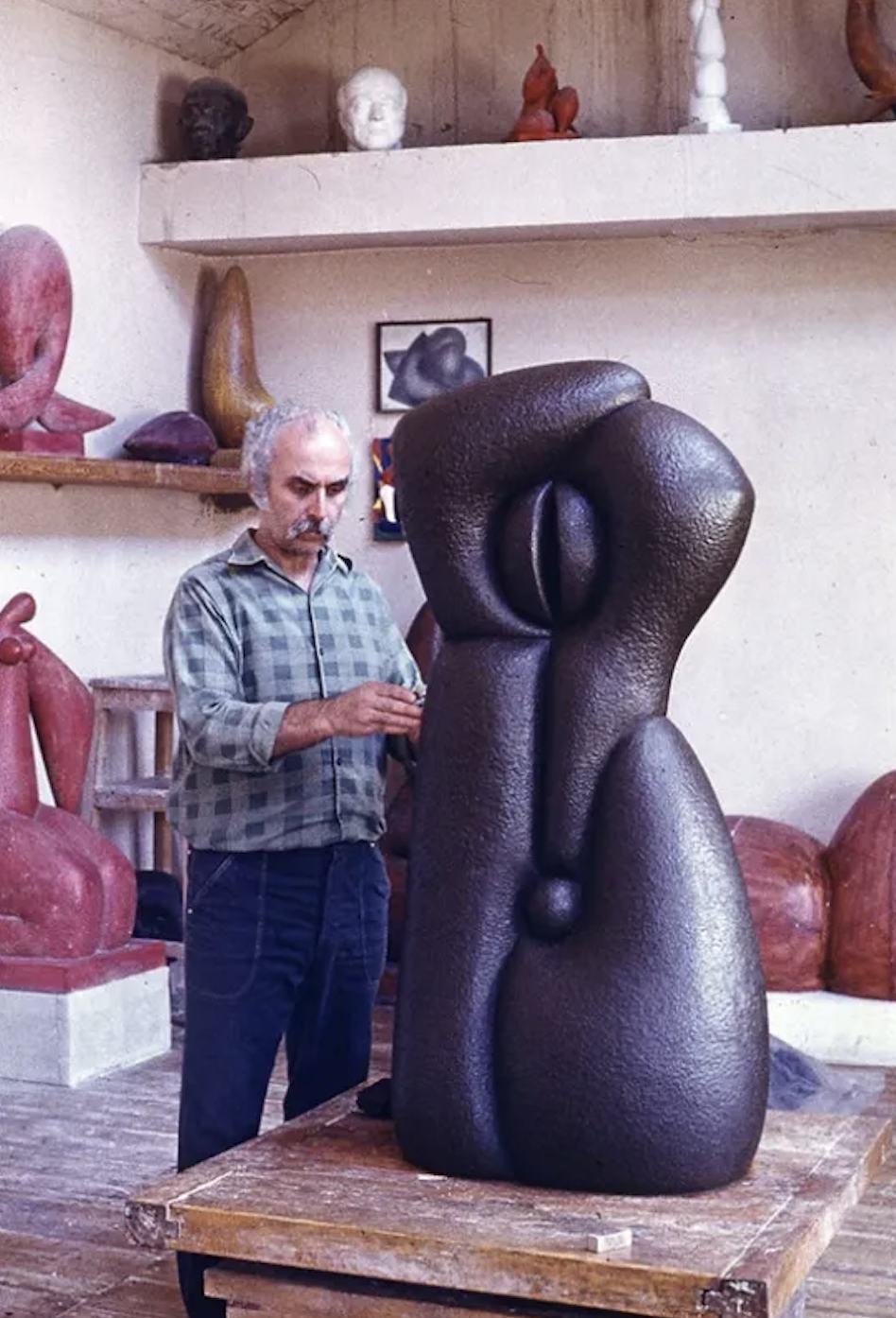

Karlo Grigolia, the sculptor's studio, Tbilisi

“Naturalism” or “Formalism?”

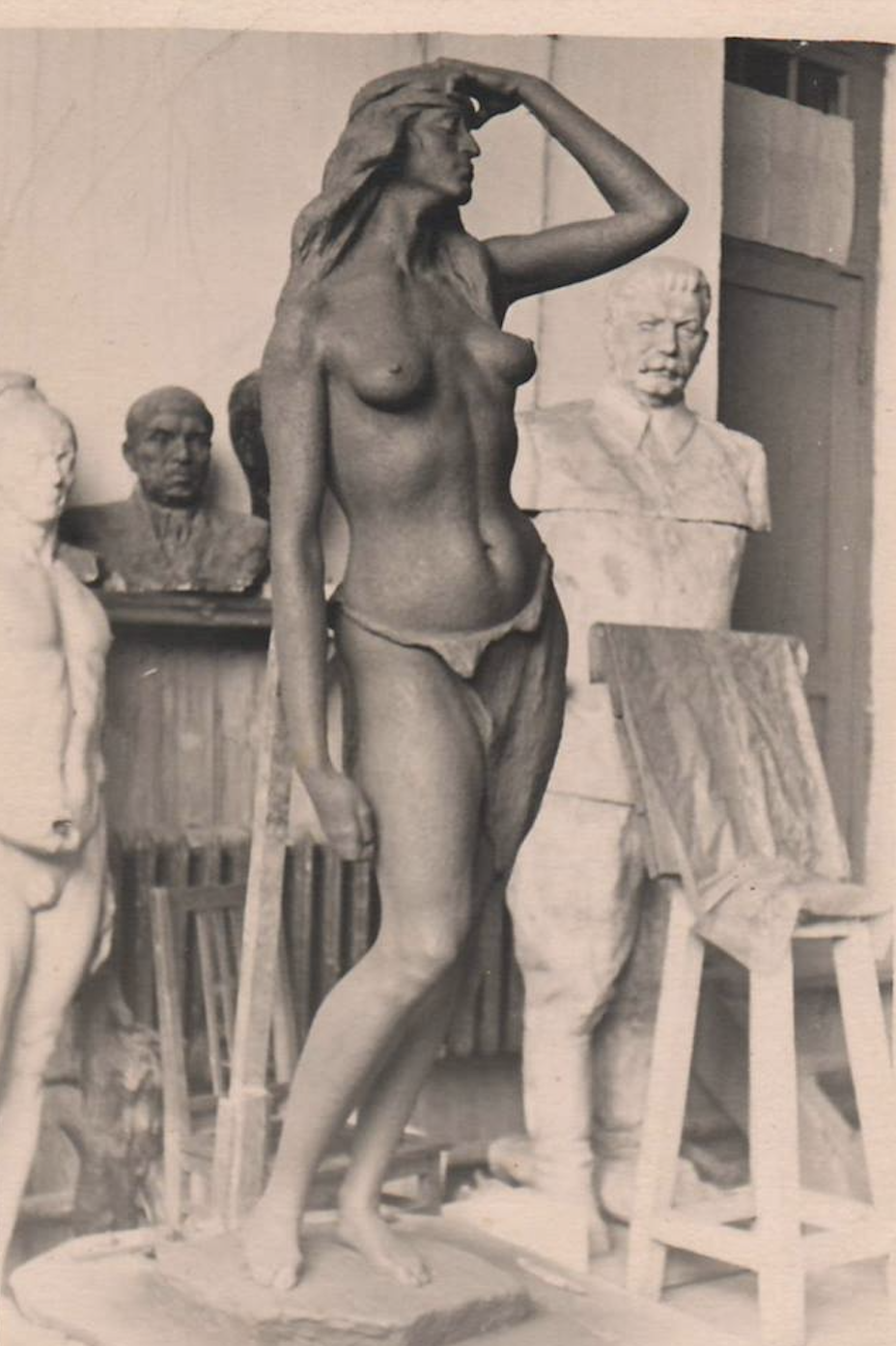

Despite continuous efforts of the professors at the Academy of Art to preserve for their students an environment of intellectual freedom, in the 1950s the Academy was under strict surveillance and control by Soviet political authorities. Their primary mission was to mold propagandists loyal to the regime. Faced with this intense political pressure, upon entering the Academy, Karlo Grigolia sought to deviate from the compulsory constraints of socialist realism as prescribed by the curriculum. The system was intolerant of such a non-conformist approach. The first blow inflicted on Karlo Grigolia by the Soviet educational system was the rejection of his graduate work, which was probably judged "naturalistic" and "formalistic," despite the fact that it had the endorsement of such a renowned artist as Sergo Kobuladze. The two terms "naturalism" and "formalism" carried highly ambiguous connotations in the annals of Soviet art history, and were frequently wielded to ruin the artist's career. The young sculptor subsequently destroyed the graduate work that had been met with disapproval. The graduate work was not accepted by the commission in 1956. The sculptor subsequently destroyed the work. It is preserved only in archival photographs. Venue in the photo: Tbilisi State Academy of Art, Sculptors’ class.

Karlo Grigolia. Persecution

Despite the "ottepel" of the 1960s (the era of reduced repression and censorship known as the Khrushchev Thaw), which allowed non-conformist and underground art to appear in the USSR, the situation within the country nonetheless remained difficult. Surveillance and repression took on a different guise from that experienced during Stalin's period, but did not disappear completely. As a result, for an extended period Karlo Grigolia, like many others, continued to face significant pressure from the system. He frequently encountered rejections for participating in exhibitions, and the state extremely rarely acquired his works, usually after the sculptor's heated argumentation, deliberately placing him in challenging financial circumstances. At meetings of the Union of Artists, which the sculptor had been a member of since 1960, his colleagues and defenders of the system referred to him as an artist and citizen with anti-Soviet ideas, which constituted a basis for societal pressure and a pretext for the sculptor’s further marginalization. Karlo Grigolia also had supporters who strove to assist him at their own peril. Their efforts did not go unnoticed, and they frequently found themselves at odds with the system. But nevertheless, despite these challenges they remained steadfast in their support for Karlo Grigolia. His Georgian colleagues, who fully grasped the significance of the sculptor's work, did not waver in their determination to assist him. Amidst such persecution, Karlo Grigolia only managed to physically survive because he never directly engaged in politics. Instead, he adopted a different strategy; he realized that reforming Georgian sculpture would help in the struggle against the regime. His approach involved renewing the language of art so as to convey to the public the notion of a different and liberated world. He was prepared to endure persecution for this idea. The sculptor channeled all of his energy into his creative processes, and refrained from becoming entangled in social and political provocations. He even succeeded in incrementally including his modernist portraits in the prominent annual spring and autumn exhibitions, thereby contributing significantly to Georgian sculptors and their audience. Through his own creative efforts, he made modern art available, even though it remained inaccessible behind the Iron Curtain and was prohibited in Georgia. Nonetheless, to the censors he frequently claimed that his portraits were realistic works of art.

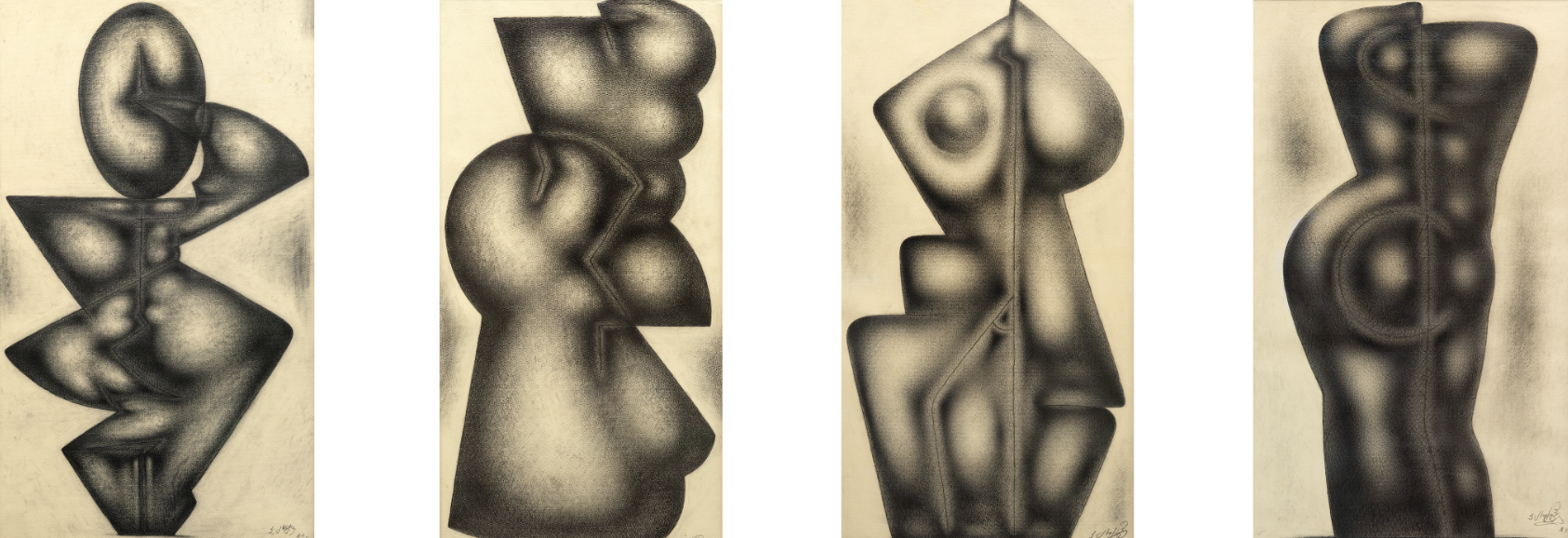

Karlo Grigolia. Drawings

The system took revenge by imposing complete silence upon him. Until the 1980s, there were no journalistic or professional reviews, analytical evaluations, or articles about Karlo Grigolia. He remained absent from the chronicles of Soviet art history. An article that introduced him as a sculptor was prepared and published in issue #12 of the magazine 'Soviet Art' by Elguja Amashukeli – a Georgian sculptor who enjoyed significant social, cultural, and political influence. Elguja Amashukeli, along with figures such as Sergo Kobuladze, Apollon Kutateladze, Zurab Tsereteli, and other prominent representatives of Georgian art and culture, made numerous efforts to support Karlo Grigolia and provide him with the opportunity of fully engaging in modern sculpture. Elguja Amashukeli seized the opportunity that was presented by the weakening of the Soviet government, and in 1982, along with his associates, he persuaded the Government of Georgia to erect two abstract sculptures by Karlo Grigolia in the square in front of Kashveti Church, which is now known as 9th April Park (by the time the sculptures were erected known as the Park of the Communards). Despite the weakening Soviet system, Elguja Amashukeli was summoned to the Central Committee of the Georgian Communist Party as a result of his involvement in erecting the sculptures created by Karlo Grigolia.

As the 1980s drew to a close, the Soviet regime began to lose its power. In a relatively stable political climate, the efforts made by Georgian artists and the distinguished artistic skill of Karlo Grigolia held the potential for bringing the non-conformist sculptor out of the shadows. Unfortunately, shortly afterwards the 1990s 'perestroika' era began, and the country was plunged into an extended period of political turmoil amid its newfound freedom. The Soviet totalitarian regime had not been able to stop Karlo Grigolia at that time, and could not stop him now, either. Every day until he passed away, he actively worked in his studio. For K. Grigolia, sculpture transcended a mere profession; he regarded it as a calling. From this was engendered his tremendous perseverance and great devotion to the field.

Karlo Grigolia passed away in 2014. Before his death, the sculptor had headed the Association of Avant-Garde Artists of Georgia. He was a member of the International Sculpture Center (ISC) in the US. Since 2001, Karlo Grigolia's work has been preserved in the permanent collection of the State University of New York at Fredonia. We previously mentioned supporters of the sculptor, but we have to admit that the main “accomplices” were his family members. Two generations of the Grigolia family devoted their lifetime to preserving his works and bringing his legacy back to society.

Portrait of Elguja Berdzenishvili. 34x27x25. Plaster

Portrait of Karina Wamling. 32x24x26. Plaster. 1990

Motives of Nonconformity

Karlo Grigolia's art underwent significant evolution over the years. His non-conformist spirit and resistance to the system are evident from various instances during his lifetime, but two occasions stand out notably. The first occurred when as a Soviet citizen, he was given the opportunity to remain in Italy for good, and thus to escape the regime. The sculptor declined the offer, adhering to his characteristic prioritization of professional integrity over material wealth and comfort. He remained unwavering and uncompromising in this stance. Creating outside the realm of Georgian culture was inconceivable for Karlo Grigolia, since this cultural and geographical space served as the axis of his assertion: “Georgia, a country of volcanic origin with towering mountains, passes and peaks, symbolizes the profound internal energy within us – tightly bound and unyielding. That's why the Georgian nation is remarkable for its tremendous vitality: a gift bestowed upon us by our land and our environment. From my point of view, my sculptures represent the physical embodiment of our national spirit. I believe that sculpture should both stem from our cultural roots and be necessarily linked to cosmic, astral contemplation – signifying our journey towards perpetual development.”

The sculptor's second manifestation of non-conformity came to define his entire life. He never embraced the values of the Soviet Union, nor did he ever desire to work within the confines of their prevalent and established artistic style – socialist realism. During the era when the Soviet authorities mobilized tens of thousands of talented artists to promote their visual propaganda throughout the Union, Karlo Grigolia embarked on a daring and nonconformist quest to explore truths beyond the confines of the socialist ideals that were upheld by the Soviet regime.

Karlo Grigolia was totally alienated from the phantom nature of socialist realism and socialist convulsions. As he wrote: "My entire creative endeavor embodies an organic fusion of the creator with the planet and nature. The earth itself serves as the supreme creator. As such, I perceive the fundamental essence and embodiment of sculptural principles within nature. I view our planet in space as a comprehensive sculpture, with its inner impulse serving as the life force of humanity. That's why my sculptures convey a profound internal, volcanic energy; their forms are charged in much the same way as the nucleus of an atom: emanating an unmistakable inner force. I focus mainly on the plasticity of form and aesthetics. For this reason, I adhere to the fundamental classical principles of sculpture. In doing so, I aim to give modern sculpture back its spoken language.” Even from this brief excerpt, it is evident how cohesive, well-considered, and organized the sculptor's position was. Karlo Grigolia raised such pertinent and significant questions within the context of the history of Georgian sculpture that he called into question the value of the collectivized and impersonal culture of the Soviet system itself.

Abstract Art - an Agent of Deconstruction

Karlo Grigolia's investigation into the infinite energies that predicate the universe prompted his shift from figurative sculpture to more abstract forms. From this point on, as he delved into abstract sculpture, his creative work would align with the principles of modernist art that were proscribed within the borders of the Soviet Union. Similar to abstract art in general, Karlo Grigolia's abstract sculpture was freed from any overt symbols of socialist life and existence. He distanced himself from the state's self-centered pursuit of a "communist paradise" for the masses, instead reestablishing Georgian sculpture within the realm of personal communication with the viewer. Indeed, abstract sculpture represents the most personalized, and consequently, entirely anti-Soviet manifestation of a non-prescriptive, non-ideological, and intimate connection between an object and its viewer. As singular as Karlo Grigolia's sculpture is, it enables the viewer to attain a personal experience: to delve into one's inner self, and find meaning within, thereby serving as an instrument of deconstruction for one of the central tenets of communist ideology - collectivism.

Karlo Grigolia. Plastic form. 10x147x35. Bronze

Beyond the Patriarchal Gaze

It is of interest that a recurring theme in Grigolia's art – the energy of the universe – consistently assumed the form of a woman. In the early stages of his creative oeuvre, one could discern bodies infused with female energy in his plastic art: a theme that gradually evolved into abstractions and ultimately transformed not into abstract feminine figures, but into voluminous compositions representing female energy in abstracted form. Upon analysis of Karlo Grigolia's plastic art, it becomes evident that he regarded the energy responsible for creating the world as sexual energy. While it may appear that his gaze directed toward women was somewhat masculine in essence, the female figures he crafted, especially the graphic or abstract plastic compositions, demonstrate that Karlo Grigolia did not merely intend for us to appreciate the female body, nor did he view it as a mere object; he regarded the female body not as a mundane source of new life, but as the embodiment of cosmic energy. He removed the female body from the scrutiny of conventional masculine culture, and liberated it from the roles that are typically assigned by patriarchal society. It was another revolt against the austere, ascetic, unified, and extremely patriarchal Soviet culture. In Soviet visual culture, the female body underwent various stages of representation. At times it was artificially masculinized, and at others artificially feminized: in line with prevailing Soviet cultural policies. However, a woman was never portrayed as liberated or in control of her own body and sexuality. Against the backdrop of parallel processes in Soviet art, Karlo Grigolia's works subverted the established image of a Soviet woman that had been designated by the Communist Party. Alongside his personal democratic principles, in Karlo Grigolia's attitude towards women one can discern his connection to the values of pre-Soviet Georgian culture. At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, Georgians journalists had already highlighted the necessity for women's emancipation. During the same period, Georgian culture laid the theoretical groundwork for modernism – which had gained a successful foothold within Georgian society, but was abruptly halted upon the accession of the Soviet government. Karlo Grigolia's artwork is rooted in Georgian modernism, and he perpetuates his artistic endeavors through a dialogue with Georgian modernists – further advancing the inquiries that had been initiated by this movement.

Karlo Grigolia. Plastic Composition. 45x21x12. Bronze. 1959

Karlo Grigolia. Plastic Composition. 1963

Karlo Grigolia. Plastic Composition. 67x40x15. Bronze. 1980. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Karlo Grigolia. Plastic composition. 62x30x12. Plaster. 1986

Karlo Grigolia. Plastic Composition. 47x25x14. Plaster. 1995

Modernist Method

His collection of sculptural portraits once again confirms Karlo Grigolia as a modernist artist. He employs the techniques of modernism, and delves into sculpture from the ancient world: a realm beyond the confines of Western culture. The renewal and complete reorganization of European sculpture stemmed from a modernist aspiration to transcend the obsolete traditions of European sculpture through an appreciation and understanding of the customs of ancient civilizations. In the portraits created by Karlo Grigolia, one can discern the sculptor's thorough exploration, plastic interpretation, and incorporation of sculptural traditions from Mesoamerican, African, Egyptian, Mesopotamian, and Achaemenid Persian cultures. This method enabled him to overcome the requirements of a sculptural portrait as dictated by socialist realism: faces that were excessively poeticized and aestheticized, or vice versa: future-oriented, a stern and resolute gaze, with no emotional gradations apart from the key solid and imperative expressions. Conversely, Karlo Grigolia's gallery of portraits adeptly harmonizes individual and societal common to all mankind cultures, thereby fulfilling the objectives of plastic art. “I lay great emphasis on the sculpture's uniqueness, volume, and architecture. The "egg" as a completely flawless shape, and full of living impulses, is my ideal. I'm attempting to create not simply a new shape, but also a new way of thinking on a large scale.”

Karlo Grigolia. Self-portrait. 32x27x23. Bronze. 1960

Karlo Grigolia tirelessly dedicated himself to researching the language of plastic arts, thereby guiding Georgian artists toward a rediscovery of their artistic purpose. He bequeathed us with extensive insights into the realm of artistic endeavors, and upon encountering his work, his words strike a particular chord with everyone who delves into his oeuvre:

"I am among those in the world who have contributed to the creation of plastic art" - Karlo Grigolia